On Solana, “same-block execution” sounds deceptively simple, until you actually try to achieve it. Traders miss arbitrage windows by milliseconds, liquidations land one slot too late, and carefully engineered transaction chains fall apart under real network load. In a system designed for extreme parallelism and speed, the idea of forcing multiple actions to happen in the same block becomes a game of probability, not intent.

Understanding why this happens and where the real technical limits are—it’s the difference between winning and losing MEV races, between reliable protocols and flaky ones, and between infrastructure that looks fast on paper and infrastructure that actually performs under pressure.

What “same-block execution” really means on Solana (not Ethereum)

For engineers coming from Ethereum or other EVM-based chains, the phrase same-block execution carries an implicit promise: if multiple transactions land in the same block, their order is known, execution is deterministic, and state transitions are easy to reason about. On Solana, this mental model breaks almost immediately.

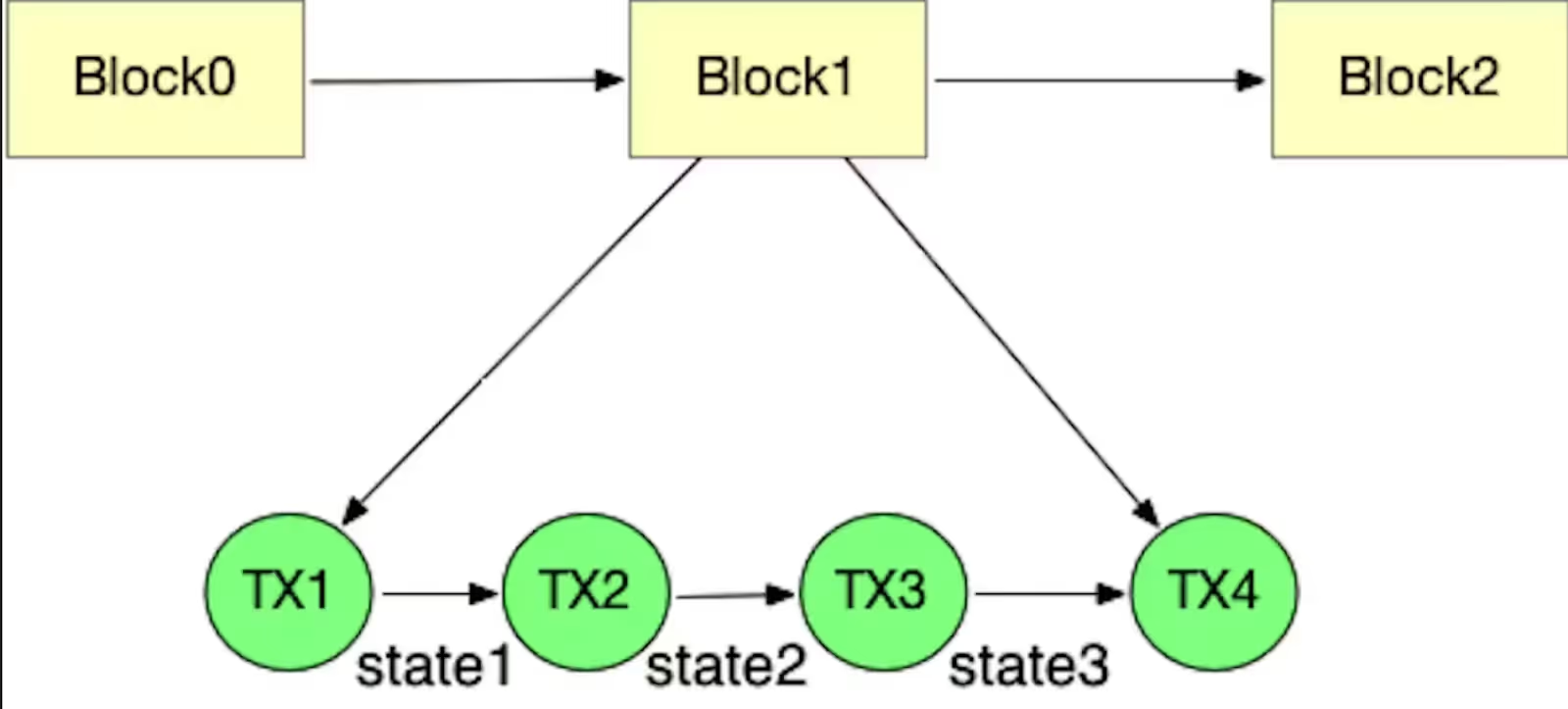

First, the word block itself is misleading. Solana does not operate with discrete, slow-forming blocks in the Ethereum sense. The fundamental unit of time is the slot, which lasts roughly 400 milliseconds. During each slot, a single validator—the leader—is responsible for receiving transactions, executing them, and producing entries in the Proof of History (PoH) sequence. What users casually call a “block” is, in practice, the output of one or more banking stages inside a slot, potentially across forks, before finalization.

This distinction matters because execution on Solana is continuous, not batch-based. Transactions stream into the leader’s pipeline, are verified, scheduled, and executed as soon as resources are available. There is no global moment where “the block is closed” and ordering becomes fixed. As a result, two transactions can:

- be submitted during the same slot,

- be executed by the same leader,

- and still observe different intermediate states depending on scheduling, account locks, and thread availability.

Another critical difference is the absence of a global public mempool. On Ethereum, users and searchers can see pending transactions, reason about their relative ordering, and build bundles with strong assumptions about inclusion. On Solana, transactions are sent directly to the current (or upcoming) leader via the TPU. Visibility is fragmented, timing is opaque, and inclusion depends far more on network position and leader proximity than on intent.

When Solana developers talk about same-block execution, they are usually referring to one of three very different goals:

- Same-slot inclusion—multiple transactions landing within the same leader slot.

- Relative ordering—one transaction executing before another.

- Atomic state visibility—later instructions observing the effects of earlier ones.

On Ethereum, these three often come together by default. On Solana, they are separate problems, each with its own failure modes. Achieving all three simultaneously is not guaranteed by the protocol—and never has been.

Solana execution pipeline: Where same-block guarantees break

To understand why same-block execution on Solana is fragile, you have to stop thinking in terms of “transaction inclusion” and start thinking in terms of pipeline pressure. Solana is not a queue that processes transactions one by one—it is a high-throughput execution conveyor belt, and every stage in that belt can silently break your assumptions.

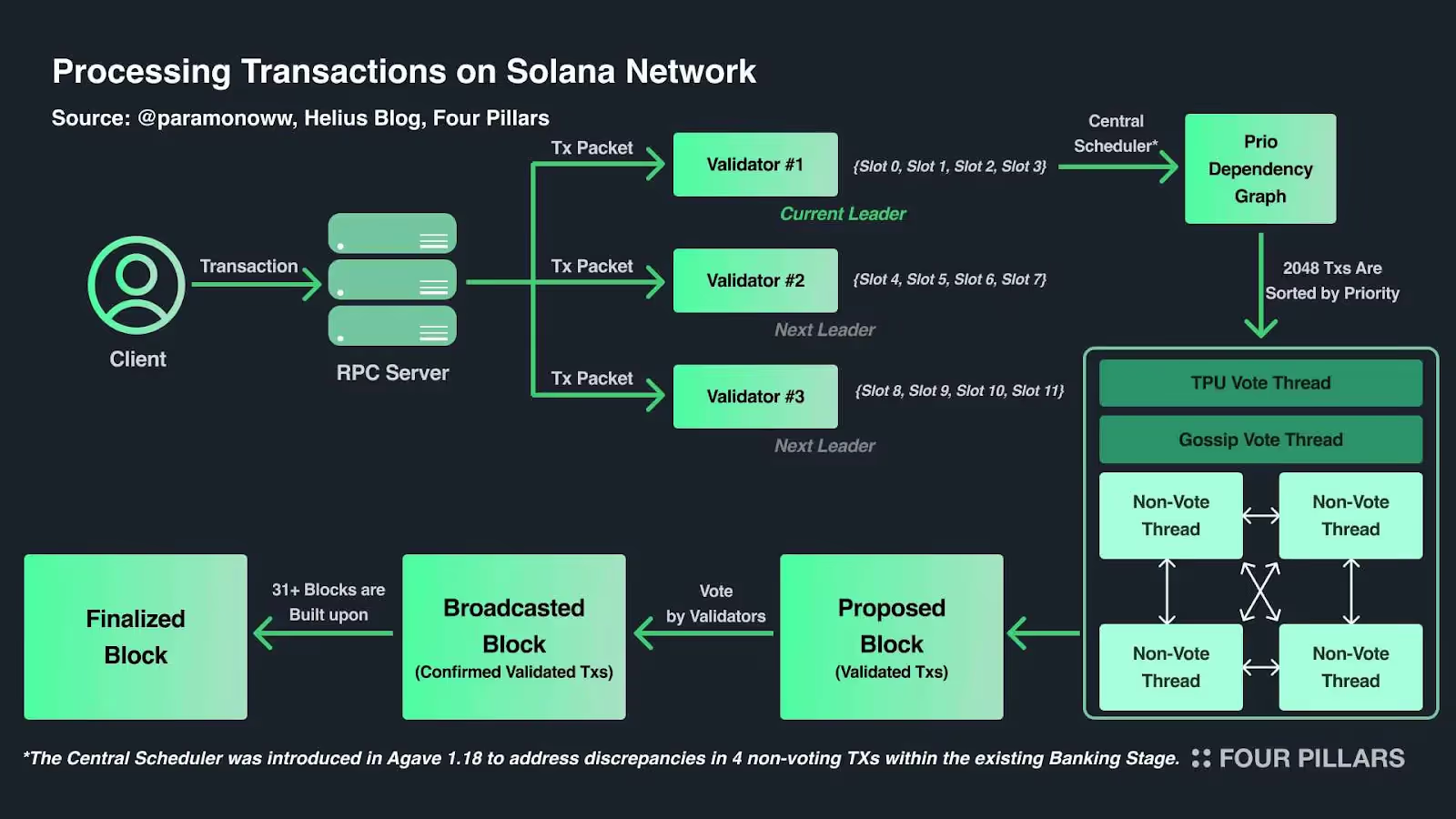

A transaction’s life begins at the RPC layer, but this is already the first point where guarantees weaken. When a client submits a transaction, the RPC node does not place it into a global waiting room. Instead, it forwards the packet toward the Transaction Processing Unit (TPU) of the current or upcoming leader. At this moment, the only real guarantee is best effort delivery. Packet loss, retransmission delays, and routing inefficiencies can already push a transaction into the next slot—even if it was signed “on time.”

Once a transaction reaches the TPU, it enters the SigVerify stage. Here, signatures are verified in parallel, and invalid transactions are dropped early. Under high load, this stage becomes a filter rather than a queue. Transactions are not processed strictly in arrival order; they are processed based on thread availability. Two transactions submitted back-to-back can diverge here, with one progressing and the other stalling or being retried.

The next major break in guarantees happens in the Banking stage, which is the core of Solana’s execution model. The banking stage schedules transactions across multiple threads and executes them optimistically in parallel. Before execution, each transaction declares which accounts it will read from and write to. If two transactions contend for the same writable account, only one can proceed. The other is not “queued behind it” in a deterministic way—it is deferred, retried, or skipped depending on scheduler timing and load.

This is where same-block assumptions collapse most often. Even if two transactions:

- reach the same leader,

- enter the banking stage within the same slot,

- and target the same logical workflow,

their actual execution order is non-deterministic. The scheduler prioritizes throughput, not developer intent. Account locks, compute availability, and thread timing decide who runs first—not submission order, priority fee alone, or RPC proximity.

After execution, successful transactions are recorded into the Proof of History stream. Importantly, PoH does not retroactively reorder anything. It simply records what already happened. By the time a transaction is written into PoH, any opportunity for enforcing same-block ordering is long gone.

Finally, the executed state is replayed and confirmed by the rest of the cluster. At this point, failures caused by contention, retries, or starvation are already baked in. A transaction that “should have” been in the same block might appear one slot later—or fail entirely—with no explicit error pointing to ordering as the cause.

The key takeaway is this: there is no single moment in Solana’s pipeline where same-block guarantees can be enforced globally. Each stage optimizes for speed and parallelism, and each stage introduces uncertainty. Same-block execution does not fail because of one flaw—it fails because the system is explicitly designed to avoid the very synchronization points that deterministic ordering would require.

Account locks, parallelism, and the illusion of deterministic ordering

At the heart of Solana’s performance lies its account-based parallel execution model—and this is also where most same-block assumptions quietly die. Unlike EVM chains, where transactions execute sequentially against a global state, Solana treats transactions as independent workloads that can be processed in parallel as long as their account access does not conflict.

Every Solana transaction explicitly declares:

- read-only accounts,

- writable accounts.

Before execution, the runtime attempts to acquire account locks:

- Multiple transactions may hold read locks on the same account.

- Only one transaction may hold a write lock on a given account at any moment.

This sounds deterministic on paper, but in practice it is not.

Parallel banking threads and lock contention

The Solana banking stage runs across multiple threads (dozens per validator, depending on hardware). Transactions are assigned to threads optimistically, not sequentially. If a thread attempts to execute a transaction and finds that a required write lock is already taken, that transaction is aborted and retried later, potentially in the same slot—or the next one.

Crucially:

- There is no FIFO queue per account

- There is no guaranteed retry order

- Lock acquisition depends on thread timing at microsecond granularity

Two transactions targeting the same writable account can arrive in the same slot, yet execute in different orders across different validators or different runs. This is why Solana cannot provide deterministic intra-slot ordering guarantees.

Real-world failure modes

This model creates subtle but costly issues in production systems:

- DEX workflows: a swap followed by an arbitrage tx may execute in reverse order.

- Liquidations: a liquidation tx may miss priority because the debt account is already locked.

- NFT mints: mint + metadata update races fail unpredictably.

- MEV strategies: sandwich legs land in different slots under contention.

Even priority fees do not fully solve this. While higher ComputeUnitPrice increases the chance of being scheduled, it does not override lock conflicts. A low-fee transaction with a free lock can execute before a high-fee transaction that is blocked.

Numbers that matter

- Slot time: ~400 ms

- Typical lock contention retry window: 10–100 ms

- Banking thread count: scales with CPU cores (often 16–64 threads)

- Result: micro-timing differences dominate over submission order

The uncomfortable truth is this: on Solana, ordering is an emergent property, not a rule. If your system relies on “transaction A must execute before transaction B,” and they are not part of the same instruction flow, you are already operating on borrowed time.

Why RPC alone cannot guarantee same-block execution

When same-block execution fails, RPC providers are often the first to be blamed. Faster RPC, lower latency, better routing—surely that should fix it? In reality, RPC is only responsible for getting your transaction to the validator, not for deciding what happens next.

What RPC actually controls

A high-performance RPC can meaningfully improve probability, but not guarantees. Specifically, RPC can:

- Reduce submission latency (p50, p95)

- Fan out transactions to multiple TPU endpoints

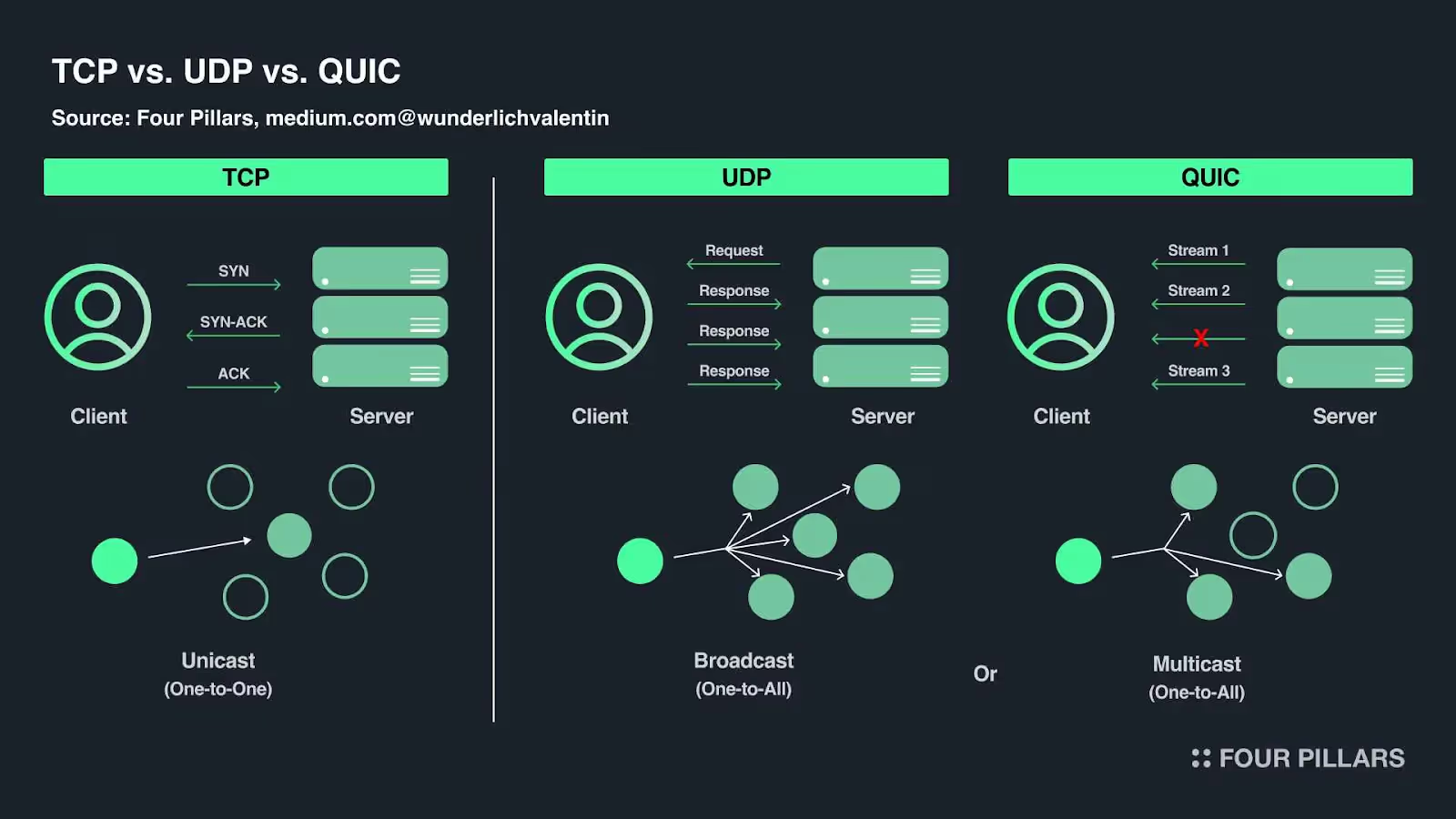

- Use QUIC instead of UDP for better packet delivery

- Pre-simulate transactions to avoid obvious failures

These improvements matter. Shaving 20–40 ms off submission time can be the difference between landing in the current slot or the next one. But once the transaction reaches the leader, RPC influence effectively ends.

What RPC cannot control

RPC has zero authority over:

- Banking stage scheduling

- Account lock resolution

- Thread assignment

- Intra-slot execution order

- Compute starvation decisions

There is no RPC API for:

- “Execute this before transaction X”

- “Force same-slot execution”

- “Reserve a write lock in advance”

Once a transaction enters the leader’s TPU, it competes on equal footing with:

- transactions from other RPCs,

- transactions sent directly by searchers,

- validator-internal traffic,

- bundle submissions (e.g. Jito).

At that point, execution is governed entirely by the validator runtime.

The latency fallacy

A common misconception is that lower latency equals guaranteed ordering. In practice:

- A transaction that arrives 5 ms earlier can still lose a lock race.

- A transaction that arrives later can execute first if its accounts are free.

- Retry timing can invert intended order within the same slot.

RPC reduces network uncertainty, not execution uncertainty.

Practical implication

RPC should be viewed as a probability amplifier, not an execution oracle. The best RPC infrastructure increases:

- same-slot inclusion rate,

- retry success rate,

- consistency under load.

But no RPC—no matter how fast—can force Solana to behave like a sequential system. Expecting same-block guarantees from RPC alone is a category error. Reliable systems are built by designing with Solana’s execution model, not by trying to overpower it with faster pipes.

The role of leaders, TPU routing, and network topology

If same-block execution is a probability game, then the leader is the house. On Solana, the validator scheduled as leader for a given slot has near-total control over which transactions even get a chance to execute. Everything before that point—RPC speed, retries, fees—only determines whether your transaction reaches the leader in time.

Leader slots and timing windows

Solana’s leader schedule is known in advance, usually several epochs ahead. Each leader controls a continuous window of slots (typically 4 consecutive slots, ~1.6 seconds total). However, this does not mean you have a full 400 ms to submit transactions safely. In reality:

- The effective submission window is often 100–200 ms

- Late packets are pushed into the next slot or dropped

- Congestion shrinks this window even further

This makes leader-aware submission critical. Sending transactions blindly to a random RPC endpoint adds unnecessary hops. Each extra network hop (5–15 ms) directly reduces same-slot inclusion probability.

TPU routing: direct vs indirect paths

Transactions reach leaders through the Transaction Processing Unit (TPU). There are two main paths:

- Indirect: Client → RPC → gossip → TPU

- Direct: Client / RPC → leader TPU (known address)

High-performance setups aggressively favor direct TPU fan-out, often sending the same transaction to:

- current leader

- next leader

- sometimes the leader after that

This redundancy increases delivery probability but introduces its own trade-offs:

- Packet duplication

- Retry storms

- Higher network load under congestion

Transport layer matters

Most modern Solana infra has moved from raw UDP toward QUIC:

- Better congestion control

- Lower packet loss

- More predictable latency under load

However, QUIC does not make execution deterministic. It only improves arrival reliability. If a transaction arrives reliably but hits a locked account or a saturated banking thread, it still loses.

Geography is not a detail

Latency is not abstract on Solana—it is slot math.

- 10 ms = ~2.5% of a slot

- 40 ms RTT penalty can move you from “early” to “too late”

This is why serious MEV and latency-sensitive systems colocate:

- RPC nodes

- TPU senders

- validators in the same regions (often Ashburn, Frankfurt, or Amsterdam).

The uncomfortable reality: network topology can matter more than fee bidding. A perfectly priced transaction sent from the wrong region can lose to a cheaper one that simply arrived earlier.

Compute budget, CU limits, and execution starvation

Even if your transaction reaches the leader on time and avoids account lock conflicts, there is another silent killer of same-block execution: compute starvation.

Every Solana transaction consumes Compute Units (CU). By default, a transaction is limited to 200,000 CU, but programs can request more via the ComputeBudget instruction, up to a protocol-defined maximum (currently 1.4M CU per transaction).

Slots are compute-constrained, not time-constrained

A common misconception is that a slot is “open” for 400 ms and can execute anything that fits in that time. In reality, slots are bounded by:

- total available compute

- number of banking threads

- per-thread execution capacity

Once a slot’s compute budget is effectively saturated, additional transactions are deferred, even if they arrived early.

Priority fees ≠ guaranteed execution

Solana’s fee market uses:

ComputeUnitLimitComputeUnitPrice(priority fee, in micro-lamports per CU)

Higher priority fees increase scheduling preference, but they do not:

- create more compute

- preempt already-running transactions

- bypass account locks

Under heavy load, this leads to priority inversion:

- High-fee transactions request large CU budgets

- They block threads longer

- Smaller, cheaper transactions slip through and execute first

Starvation failure modes

This becomes especially visible in:

- complex DEX swaps (multiple CPIs)

- liquidation bots

- NFT mint + metadata flows

- oracle-heavy instructions

A transaction may:

- pass simulation

- arrive early

- have a high priority fee

…and still fail to execute in-slot because there is no compute left when it reaches the front of a thread.

Numbers that explain the pain

- Default CU limit: 200k

- Heavy DeFi txs: 400k–900k CU

- Max CU per tx: ~1.4M

- Slot compute saturation under load: can occur in <150 ms

From the outside, this looks like randomness. Internally, it is pure resource exhaustion.

The key lesson: same-block execution is constrained as much by compute economics as by networking. If your design assumes unlimited compute availability within a slot, it will eventually fail—usually at the worst possible moment.

How RPC Fast improves probabilities without overpromising guarantees

At some point, every serious Solana team reaches the same conclusion: same-block execution cannot be forced, but it can be made less fragile. This is where infrastructure stops chasing absolutes and starts optimizing probabilities. RPC Fast is designed around this reality, not in denial of it.

The first lever is time-to-leader. RPC Fast minimizes the distance—both logical and physical—between transaction submission and the current leader’s TPU. This is not about raw benchmark latency in isolation, but about consistently arriving early enough within the leader’s effective execution window. When slots compress under load, arriving 20–30 milliseconds earlier is often the difference between execution and deferral. RPC Fast optimizes for this narrow window by reducing hop count, prioritizing direct TPU paths, and avoiding gossip-based delivery wherever possible.

The second lever is delivery reliability under congestion. Solana does not fail politely when the network is stressed. Packets are dropped, retries pile up, and late arrivals quietly slide into the next slot. RPC Fast is built to survive these conditions by favoring transport-layer stability over theoretical throughput. More predictable delivery means fewer silent failures and fewer retries competing with your own traffic. This does not guarantee inclusion, but it materially reduces avoidable loss.

The third lever is submission awareness, not execution control. RPC Fast does not pretend it can reorder transactions or override the banking scheduler—because it cannot. What it can do is aggressively filter bad submissions before they ever reach the leader. Pre-simulation, sanity checks, and rejection of obviously failing transactions reduce wasted compute and retry noise. In high-load environments, this indirectly improves execution probability by keeping the pipeline cleaner and less contested.

Crucially, RPC Fast is optimized for consistency, not miracles. The goal is not to claim “same-block guaranteed,” but to narrow the variance between best-case and worst-case outcomes. Lower variance means fewer pathological edge cases where transactions that should have landed simply disappear into retry loops or starvation. Over thousands of transactions, this consistency compounds into real performance gains.

Next step: improve your same-slot execution odds

Same-block execution on Solana can’t be guaranteed, but it can be made far more reliable. If you’re hitting missed slots, unstable ordering, or unpredictable retries, RPC Fast can help you understand where time and probability are being lost.

Talk to the RPC Fast team about your current setup. We’ll look at your routing, latency, and execution flow and show where infrastructure changes actually move the needle.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)